|

|

||

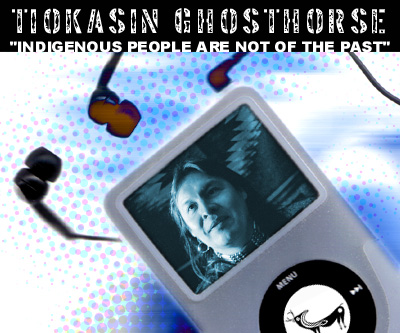

New Voices New Visions Those of us in the media supposedly seek the truth. Or what we deem to be the truth. But what or who defines our truths? How responsible are we journalists to purport the truth to our readers, our viewers, our listeners? How dependent are audiences on our versions? Do we inspire them to search out their own truths, or do we influence so well that we leave no room for doubt? “All visions of history are a point of view,” wrote Octavio Paz, Mexican poet, essayist, and winner of the 1990 Nobel Prize in Literature. But how do we know which points are valid? What colors our visions? Are there non-Indians who can relate news concerning Indigenous information without bringing into play embedded stereotyping; distorted images portrayed over and over by the media for decades? Is there a way to present the truth and still maintain that Indigenous people are not of the past, not second-class citizens? To incorporate a belief that our lives are of interest to the general populace? Of course! But, where can we find the every-day truths concerning Indigenous issues? Not just from Indian writers, but from the people themselves? Much of today’s radio programming is written by non-Indigenous people, and the programs presented by Indian people are often edited, either by tribal governments or non-Indian producers. There is definitely a need for an innovatory talk radio program where the average Indian can present his or her viewpoint without feeling pressured to curb perspective, and one man is making an indomitable fulfillment of this need. Tiokasin Ghosthorse, a member of the Cheyenne River reservation in South Dakota, presents an avant-garde radio program which allows Indigenous peoples from all over the world opportunities to offer accurate depictions of current Indigenous issues. First Voices Indigenous Radio is broadcast from the offices of WBAI 99.5 FM in New York City, every Thursday from 10-11 am Eastern Standard Time. Listeners outside NYC can tune in at www.wbai.org. In a recent conversation I asked Tiokasin why he had chosen radio as a means of communication. He answered that radio is a medium in which the sounds and the intonations of our voices are presented the same as oral culture. Growing up on the reservation, he was constantly watching and listening to the elders who were “eloquent speakers and whose abstract concepts compelled deepened thinking.” He added that those old traditionalists were “truly philosophers and intelligentsia in the sense of quantum physics thinking,” and the way they spoke about their connectiveness was the true Indigenous thinking process we are all born with inherently. “I was mesmerized by the cadence of their voices, both the grandmothers and grandfathers whose involvement, experiences and evolvement with the natural world came through their vocabulary.” For Tiokasin, radio became those “mesmerizing voices” as well as a way to “bring the thought processes of the Indigenous peoples to the medium of frequency modulation and into the living rooms, kitchens, back yards and automobiles.” The program is vital in that it bridges the current struggle of scarce resources allowing Indigenous peoples the chance to be coherent in their situation of resisting through inherent rights. Tiokasin tries to avoid the safe mentality of beads, feathers, moccasins and spiritual gurus. He believes that the stereo biased perspective of the “Native American Indian” has worn out its professional life and the bastardizing of the essence of struggle. He explained: “An oxymoronic view of being Native American only plays into the internal destruction of misidentity. We often times think too much in the colonialization of the image instead of seeing the Seventh Generation our ancestors were prophesying. So the disturbing aspect of Native people is our ignorance of who we are.“ By offering Indigenous people the opportunity to share their accomplishments, ways of dealing with daily efforts, and their innermost thoughts on the thriving of their cultures, he hopes the program’s Native listeners will be empowered. Tiokasin has never had a paying job on the radio; has never been compensated for his twelve years of volunteering. He feels the responsibility and the privilege of having a voice for Indigenous peoples retains the spirit of being free. “Being paid for this work was not an idea in the initial stages, and now I think that if I were to be salaried or gifted with monetary gains, it would be for improving the First Voices Indigenous Radio and sharpening the cutting edge program.” MariJo Moore |

||

|

|

||